Nipah virus (NiV) is a zoonotic pathogen that continues to generate episodic outbreaks in parts of Asia, including India. In humans, NiV infection spans asymptomatic disease through acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis, with a case fatality rate typically cited at 40-75% (context-dependent).

For practitioners, NiV is best addressed through a One Health lens (reservoir ecology, exposure pathways, and health system readiness). In that readiness picture, WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) is not “adjacent”; it is a core layer that enables prevention and infection control at scale.

1) Epidemiology in India: recurring, localised outbreaks with spillover signatures

India’s first recognised NiV outbreaks were reported in Siliguri (2001) and Nadia (2007) in West Bengal, followed by outbreaks in Kerala (including Kozhikode 2018 and Kochi 2019).

In WHO’s Disease Outbreak News for Kerala (covering 17 May–12 July 2025), four confirmed cases (two deaths) were reported across Malappuram and Palakkad. WHO noted the cases did not appear linked, consistent with multiple spillover events rather than a single sustained chain. The same update states that no licensed vaccine or treatment is available and assesses the risk of international spread as low for that event, with no evidence of international human-to-human transmission.

2) Transmission: what “moves” the virus between hosts and settings

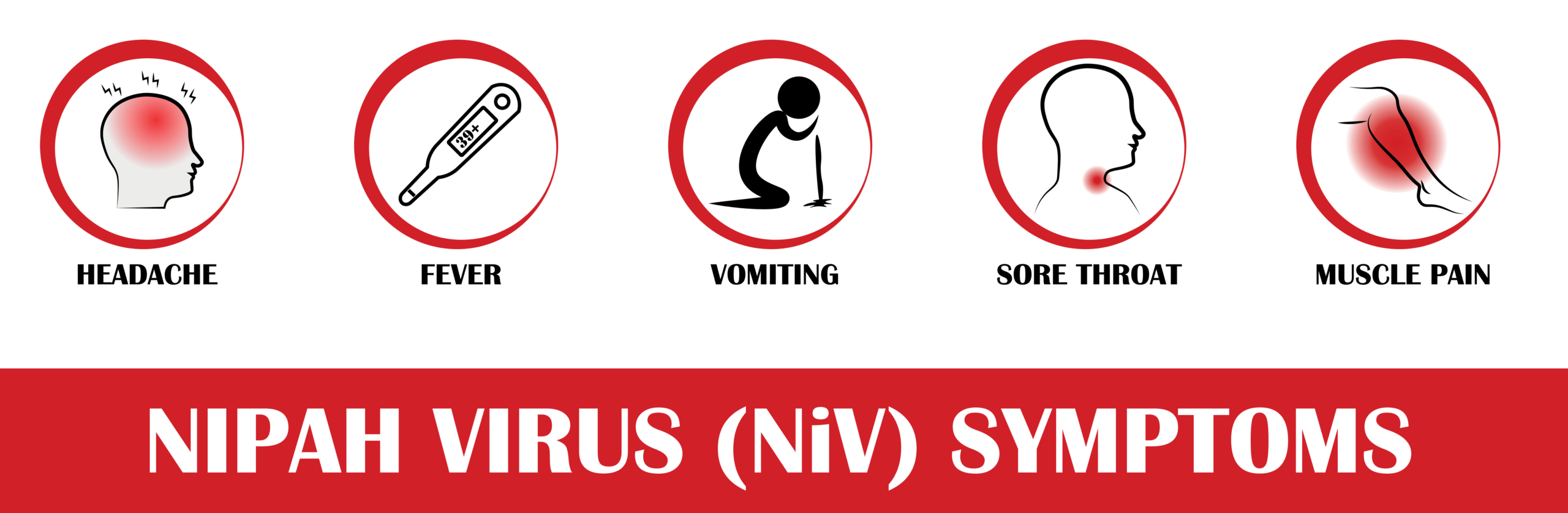

WHO summarises three principal routes of NiV transmission:

- Animal-to-human exposure (including from bats or pigs).

- Contaminated foods (exposure via food contaminated by saliva/urine/excreta of infected animals).

- Human-to-human transmission via close contact.

Fruit bats (family Pteropodidae, including Pteropus “flying foxes”) are recognised as the natural host.

Operationally, “geographic spread” is shaped less by intrinsic viral movement and more by exposure opportunities (food systems, animal interfaces) and healthcare/caregiving contact networks. The latter is why facility-level readiness remains a decisive control point.

3) Where WASH fits, enabling exposure reduction + preventing amplification

NiV is not primarily framed as a waterborne disease. However, WASH is central because it underpins two control levers that repeatedly determine outbreak size and trajectory:

A) Safe water enables safer food and domestic hygiene practices

The WHO highlights contaminated food as a transmission route and advises avoiding the consumption of fruits partially eaten by bats and raw date palm sap/juice in affected contexts.

In practice, implementing “food hygiene” requires reliable access to safe water for washing produce and cleaning food-contact surfaces – particularly in household and market settings where produce handling is frequent.

Implication for risk reduction: Safe water access is a prerequisite for translating the “avoid contaminated foods” guidance into routine practice.

B) WASH is foundational for IPC in health facilities (and care settings)

The WHO explicitly frames IPC and WASH as critical enablers of safe, scalable health service delivery in emergencies, reducing healthcare-associated infections and limiting transmission in both facility and community settings.

UNICEF similarly states that WASH (including waste management and environmental cleaning) is essential for IPC, reinforcing the operational link between infrastructure and infection prevention performance.

For NiV, this is important because close-contact transmission can occur in caregiving and healthcare settings. Facility readiness depends on:

- Continuous water for handwashing and environmental cleaning.

- Reliable supplies (soap, alcohol-based hand rub).

- Sanitation, waste management, and safe cleaning workflows.

- These are WASH system functions as much as they are IPC policies.

C) Hand hygiene remains a high-leverage IPC measure

WHO’s Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care provide the evidence base and implementation recommendations to reduce transmission of pathogenic microorganisms in clinical settings.

The “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene” framework supports operational adoption at the point of care.

Both are only implementable at scale when WASH inputs (water, hygiene stations, cleaning systems) are consistently available.

4) Readiness: integrating IPC + WASH as a capability, not a checklist item

For health systems strengthening, WHO’s IPC & WASH HERO CAPE (Dec 2025) is designed as a rapid self-assessment to evaluate IPC/WASH readiness capabilities, identify gaps, and guide improvements for outbreak response.

For organisations supporting outbreak readiness (public sector, NGOs, suppliers, and private operators), this framing is useful: investments in safe water access, sanitation, cleaning systems, and hand hygiene infrastructure are dual benefits; they support routine quality care and increase surge capacity during outbreaks.

5) Practical WASH + IPC priorities relevant to NiV response

Community/household/market interface

- Reinforce safe handling of fruit and food-contact surfaces where NiV risk messaging is active.

- Align messaging with WHO advice on avoiding bat-contaminated fruit and raw sap/juice (context-specific).

Healthcare and caregiving settings

- Ensure uninterrupted hand hygiene capacity (water + soap / ABHR) and visible adherence frameworks (e.g., Five Moments).

- Strengthen environmental cleaning, sanitation, and waste management as part of IPC execution.

- Use structured readiness assessment tools (e.g., HERO CAPE) to identify capability gaps before surge demand.

Nipah virus remains a priority because it combines high severity with zoonotic spillover dynamics and limited countermeasures (no licensed vaccine or specific treatment).

For experts and programme teams, the actionable takeaway is straightforward: WASH and IPC should be treated as integrated outbreak readiness capabilities that support exposure reduction, protect health workers, and reduce the risk of care-setting amplification.

References

- WHO. Nipah virus – Fact sheet (clinical presentation, CFR, transmission, countermeasures).

- WHO. Disease Outbreak News: Nipah virus infection – India (6 Aug 2025) (Kerala event summary; risk assessment; no international H2H evidence in that event).

- WHO. Disease Outbreak News: Nipah virus disease – India (India outbreak history; WHO advice).

- WHO. IPC and WASH in health emergencies (operations page) (IPC/WASH as critical enablers).

- UNICEF. WASH and infection prevention and control in health-care facilities (WASH essential for IPC; cleaning/waste).

- WHO. IPC & WASH HERO CAPE (17 Dec 2025) (readiness assessment tool).

- WHO. Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care + Five Moments for Hand Hygiene.